-

Definitions

Prevalence of Cyberbullying

This section of the research summary focuses on what we know about the prevalence of cyberbullying in general and certain forms of sexual cyberbullying (sexting and cyberdating abuse). Unless otherwise specified, the prevalence rates are based on general population samples of U.S. teens. Hence, they may underestimate the prevalence of cyberbullying among populations likely to be at elevated risk such as youth who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work.

-

Cyberbullying

-

Sexting

-

Cyberdating abuse

Risk and Protective Factors

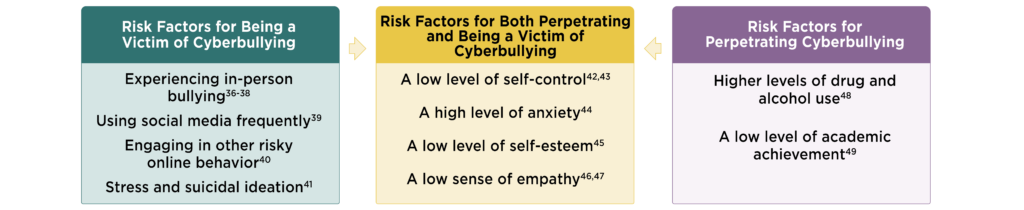

Identifying risk and protective factors specific to sexual cyberbullying is challenging because research on sexual cyberbullying is limited and often fails to distinguish between (1) sexual cyberbullying and cyberbullying that is nonsexual in nature or (2) behaviors that occur in-person and those that occur online. Consequently, this section provides an overview of factors that increase young people’s risk for or protect them against cyberbullying in general (Figure 1) and specific forms of sexual cyberbullying.

Furthermore, little sexual cyberbullying research has focused on youth who have experienced the child welfare and/or juvenile justice system, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work. However, given their increased risk for in-person sexual violence,33-35 these youth may also be at increased risk for sexual cyberbullying. Therefore, youth-supporting professionals should be aware of the risk factors for sexual cyberbullying and in-person sexual violence.

When thinking about these risk and protective factors, it is important to consider other things that might be happening in young people’s lives, such as unstable living situations or unhealthy relationships that might play a contributing role, putting them at risk for cyberbullying.

Figure 1. Risk factors for being a victim of and perpetrating cyberbullying

Cyberstalking and cyberdating abuse are two forms of sexual cyberbullying; girls are more likely than boys to be the victims of both.50 Youth-supporting professionals should be particularly attentive to supporting girls and young women who have experienced this type of violence. Youth-supporting professionals should consider the societal factors, such as sex-based violence, that contribute to girls and women being more at risk and be sure not to blame them or insinuate they did anything to elicit the behavior. Risk factors for being a victim of cyberstalking include using multiple social media accounts and engaging in other risky online behavior such as socializing with strangers.51,52 Risk factors for being a victim of cyberdating abuse include having a jealous romantic partner and engaging in sexting.53,54

In-person sexual violence and sexual cyberbullying are distinct experiences but youth who experience one may also experience the other, as has been found to be the case with traditional bullying and cyberbullying.55 Moreover, although in-person and cyberstalking victimization are related, the relationship may be different for women than for men.56 For example, females who are cyberstalked first are less likely to be subsequently stalked in-person, but males who are cyberstalked first are more likely to be subsequently stalked in-person. Lastly, females who are stalked in-person are more likely to be stalked online as well.57

Community, family, and individual protective factors may buffer youth against cyberbullying broadly. Furthermore, many of the factors that protect against cyberbullying broadly, such as parental monitoring and peer support, also protect against non-consensual sexting, a form of sexual cyberbullying.58 However, there is limited research on protective factors for specific forms of sexual cyberbullying beyond sexting.

Factors that protect against being a victim of cyberbullying include a positive and safe school climate,59,60 positive parental interactions and higher levels of parental monitoring,61,62 and higher levels of peer support and sense of “fitting in.”63,64

Prevention

-

Prevention strategies for youth-supporting professionals

-

Prevention program components

Laws on Sexual Cyberbullying

The legal landscape around sexual cyberbullying is complicated and evolving quickly. At the time of publication, we are unaware of any federal statutes that criminalize cyberbullying,90 but all states have various laws that apply to bullying behaviors, and the laws in all but two states include provisions related to “cyberbullying” or “online harassment.”91

Legislating what individuals are allowed to do with sexual images or content online is challenging because sharing sexual images and discussing sexual activities online are not inherently illegal. When legislating the sharing of sexual images, states must consider the age of the sender, the intentions of the sender, and the relationship between the sender and recipient.92 Additionally, legislation to protect victims of online sexual violence varies widely across states. This brief does not place value nor assess the effectiveness of any legislation intended to regulate any cyberbullying behavior. Rather, it encourages youth-supporting professionals and youth to be aware of the laws and understand that those behaviors can be illegal and carry potentially serious consequences.

-

-

- Sexting is generally legal unless it involves sexual harassment and/or a minor.93 Sexting is not covered by any federal laws, but as of 2022, 27 states [d] had “sexting” laws.94

- Disseminating sexual photos is not illegal unless it involves a minor or occurs without the sender’s consent.95 As of 2022, 47 states had laws against “image-based sexual abuse,” which involves sending explicit images without consent to cause emotional harm to the original sender.[e], 91 In some states, this is a misdemeanor; in other states, it is a felony.96

- Forty-seven states[f] have laws to address “electronic” or “digital” stalking, but only six use the term cyberstalking in their statutes.97

-

Summary and Resources

The information in this research brief is designed to help youth-supporting professionals familiarize themselves with research about sexual cyberbullying to better support youth, especially youth who may be more vulnerable to sexual cyberbullying such as youth who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work. To supplement the research, Table 1 provides resources related to sexual cyberbullying that youth-supporting professionals can use to support youth. Table 1 includes state and national resources that are youth specific, such as hotlines, and that can be useful to youth-supporting professionals.

Table 1. Sexual cyberbullying resources

| Organization and Contact Information | Mission |

|

The Cyberbullying Research Center

https://cyberbullying.org |

Provides current information, resources, research, and technical assistance about the nature, extent, causes, and consequences of cyberbullying among adolescents. The resource is intended for parents, educators, law enforcement personnel, and all youth-supporting professionals. |

|

Trevor Project

www.thetrevorproject.org 866-488-7386 Text START to 678-678 |

A 24/7/365 national hotline that provides crisis services, advocacy, peer support, public education, and research programs. |

|

Without My Consent https://withoutmyconsent.org/resources/ |

A project under the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative protecting online privacy. Resources focus on supporting individuals who experience incidents of nonconsensual distribution of sexually explicit images. For example, there are criminal and civil solutions state by state. |

|

Cyber Civil Rights Initiative

www.cybercivilrights.org 844-878-CCRI |

A national hotline that provides support for nonconsensual pornography and online abuse with 24-hour hotline and one-on-one support for victims. Provides resources for lawmakers to draft legislation, educational resources, and a list of states with “revenge porn” laws with references to the applicable criminal statutes. |

|

California Department of Justice Cyber-exploitation

https://oag.ca.gov/cyberexploitation |

Provides support during incidents of the nonconsensual sharing of intimate media with resources for victims for image removal, tools for law enforcement, and best practices. |

|

Crisis Text Line

https://www.crisistextline.org/ Text HOME to 741-741 |

A national hotline that provides free and confidential text-based mental health support and crisis intervention. |

|

National Domestic Violence Hotline

www.thehotline.org 1-800-799-7233 |

Provides community referrals for resources related to intimate partner violence, including teen dating violence. |

|

Love is Respect

www.loveisrespect.org 1-866-331-9474 Text: loveis to 22522 |

A national hotline that is operated by the National Domestic Violence Hotline but tailored toward providing teens information about healthy relationships and resources for parents and educators. |

|

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network www.rainn.org 1-800-656-HOPE |

A national hotline that responds to a wide range of sexual victimizations with referrals to local sexual assault services programs. Provides links to opportunities for volunteering and activism. |

|

National Center for Victims: Stalking Resource Center https://www.stalkingawareness.org |

Provides resources to educate professionals on how to keep stalking victims safe and hold offenders accountable. These are not resources for victims/survivors of stalking. |

|

Online Harassment Field Manual https://onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/ federal-laws-online-harassment/ |

Summarizes how to report federal crimes; key federal laws that may apply to online abuse; and how federal copyright law may be relevant for pursuing legal action against online abuse in civil court. |

|

MaleSurvivor www.malesurvivor.org |

Provides therapists, support groups, and other resources for male survivors of sexual abuse. |

|

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children http://www.missingkids.com/cybertipline/ 1-800-843-5678 |

A national hotline for reporting child sexual exploitation, online solicitation of sexual images, and sextortion. National method of reviewing cases for law enforcement agencies. |

|

StopCyberbullying.gov https://www.stopbullying.gov/cyberbullying/what- is-it |

Provides an overview of what cyberbullying is, laws and sanctions of cyberbullying, and prevalence of cyberbullying. |

|

National Center for Youth Law: Commercial and Sexual Exploitation https://youthlaw.org/focus-areas/commercial- sexual-exploitation |

Provides resources on human trafficking and sexual exploitation. |

|

NetSmartz https://www.missingkids.org/netsmartz/home |

Operates the CyberTipline where people can report suspicions of online and offline sexual exploitation of minors. |

-

Methods

Suggested citation: Schlecht, C., Griffin, A.M., & Rosenberg R. (2024). Sexual Cyberbullying Research Summary. Child Trends. https://activatecenter.org/resource/sexual-cyberbullying-research-summary/

Footnotes

[a] Sexual cyberbullying research does not, in general, focus on these youth. Therefore, this brief includes research about sexual cyberbullying among the overall population of adolescents as well as research on sexual cyberbullying specifically among youth who have experienced the child welfare and/or justice system, homelessness, and/or disconnection from school and work.

[b] The 2023 Activate Needs Assessment, discussions with Research Alliance members, and multiple literature scans led to the decision to focus this review on sexual cyberbullying.

[c] The term “cyber” may be outdated and not relevant to youth. However, we are using it here because it is still used in the literature. Youth-supporting professionals should consider using other terms such as online or electronic or just asking youth how they refer to cyberbullying.

[d] States with sexting laws: AZ, AR, CO, CT, FL, GA, HA, IL, IN, KS, LA, NE, NV, NJ, NM, NY, ND, OK, PA, RI, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, WA, WV.

[e] States without revenge porn laws: ID, MA, SC

[f] States without cyberstalking laws: MO, NE, NY

-

References

-

Acknowledgements and About the Authors