Findings

Opportunity youth represent a diverse group of young people

In 2015, 14 percent of youth ages 16 to 24—or 5.1 million youth—were disconnected from both school and work. This estimate is in line with other published estimates of the size of the opportunity youth population for the same time period,[2] and with more recent analysis[3] of other, newer nationally representative data sources.

- Just over half of opportunity youth are female (52%).[c]

- Most opportunity youth are over 18 (80%).

- Most opportunity youth live with at least one parent. Eighty-seven percent of opportunity youth ages 16 to 18 and 55 percent of opportunity youth ages 19 to 24 live with a parent.

- Nearly half of opportunity youth are non-Hispanic White (49%), nearly one in five (19%) are non-Hispanic Black, and approximately one in four (24%) are Hispanic. The remaining 8 percent identify as another race.

- Fourteen percent of opportunity youth identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or “something else” (LGBQ),[d] compared to 10 percent of their peers who are in school or working.

8 Findings on the Sexual Health and Reproductive Health Behaviors of Opportunity Youth

Opportunity youth experience social determinants of health linked to adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes

Social determinants of health—factors such as economic stability, health care and education access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context—affect individuals’ health and quality-of-life outcomes.[4] Social determinants of health can affect both the likelihood that young people will experience disconnection from school and work and their sexual and reproductive health.

Below, we present findings related to several key social determinants of health for opportunity youth. For more information on how social determinants of health are linked to sexual and reproductive health, see Activate’s resource Incorporating Social Determinants of Health and Equity in Practice to Address Sexual and Reproductive Health for Young People Involved in Foster Care.

-

More than four in 10 opportunity youth live in poverty

-

Opportunity youth have different levels of educational attainment

-

More than one in 10 opportunity youth experience food or housing insecurity

-

Nearly three quarters of opportunity youth had consistent health insurance and a regular place to go for medical care

Opportunity youth exhibit a range of sexual and reproductive health behaviors and outcomes

Understanding the current sexual and reproductive health behaviors of opportunity youth, as well as their SRH histories, can help professionals better serve young people who are disconnected from school and work. Because the SRH outcomes of male- and female-identifying youth can differ greatly, we present findings separately for male and female opportunity youth. We also highlight notable differences between opportunity youth and their more connected peers (i.e., youth who are either enrolled in school and/or working).

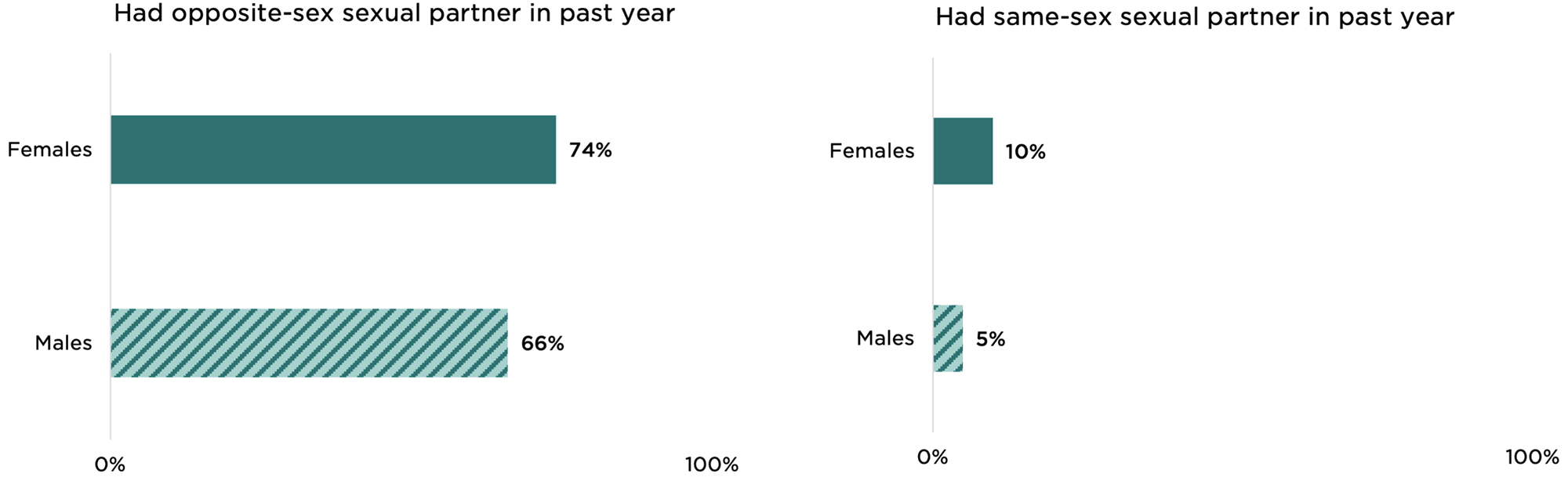

Most opportunity youth are sexually active. Around three quarters of female opportunity youth (74%) and two thirds of their male counterparts (66%) had an opposite-sex partner in the past year. Fewer had a same-sex partner (10% of females and 5% of males).

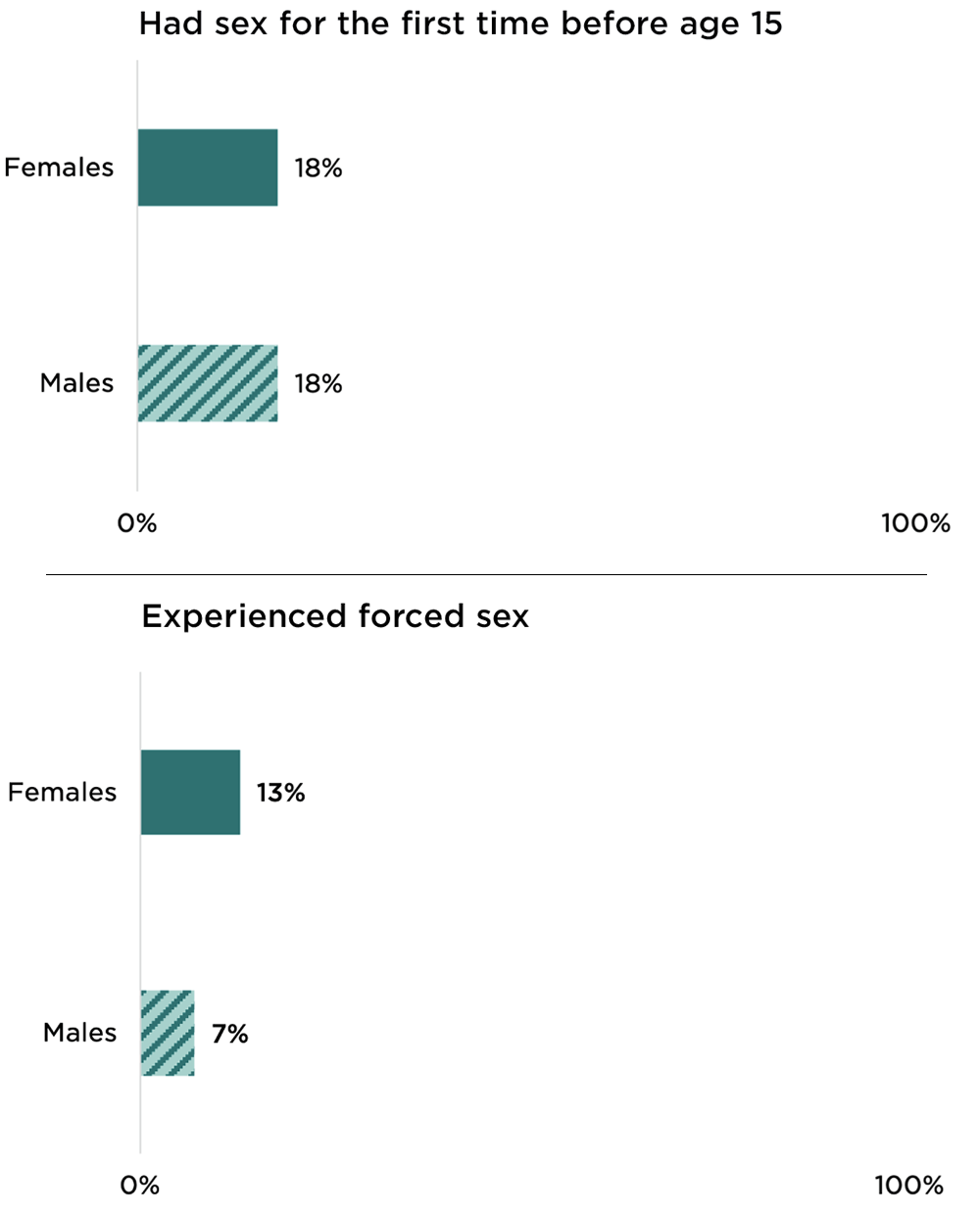

Nearly one fifth of opportunity youth experienced early sexual activity. Eighteen percent of male and female opportunity youth engaged in early sexual activity—defined as having sex before age 15. In comparison, 12 percent of youth (10% of females and 14% of males) who are enrolled in school or working engaged in early sexual activity (not shown).

About one in 10 opportunity youth have experienced forced sex. Thirteen percent of female opportunity youth and 7 percent of their male counterparts reported an experience with forced sex. We note that our analysis, based on an available data, may miss youth who have had unwanted sexual experiences. This is particularly true for female youth, as the NSFG only asks female respondents about forced vaginal intercourse with a male partner.[e]

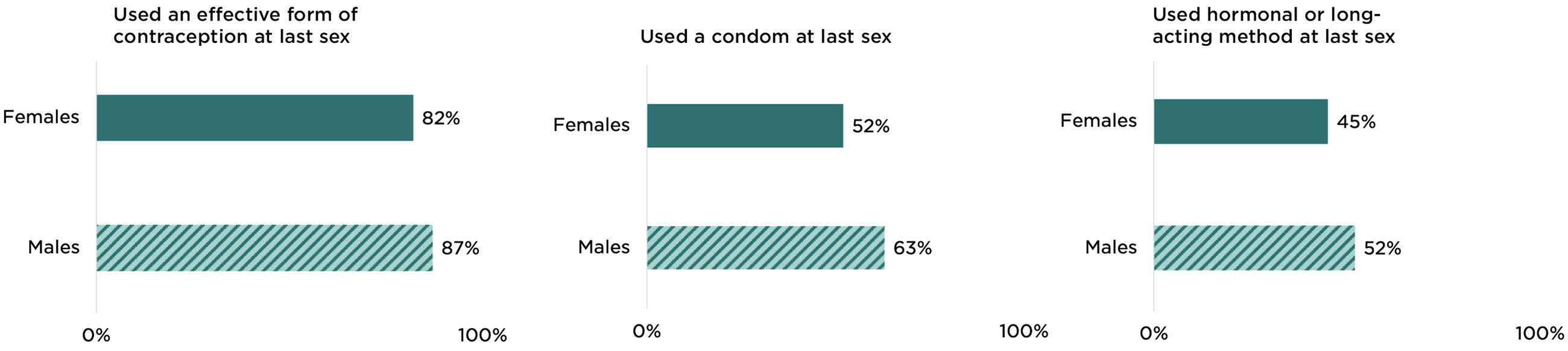

Contraceptive use is high among opportunity youth. More than 8 in 10 opportunity youth who were not pregnant (or did not have a pregnant partner) and were not seeking to become pregnant used an effective form of contraception the last time they had sex (a condom and/or a hormonal or long-acting method).[f] Approximately half (52%) of female opportunity youth and 63 percent of male opportunity youth reported using a condom the last time they had sex. Less than half of female opportunity youth (45%) reported using a hormonal or long-acting method at last sex, compared to 54 percent of their more connected peers. About half of the male opportunity youth (52%) reported that their female partner had used a hormonal or long-acting method.

Most female opportunity youth access sexual and reproductive health services. Nearly seven in 10 (69%) female opportunity youth reported receiving SRH services in the past year (not shown). These services could include gynecological services, a birth control method or counseling, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing or treatment, pregnancy testing, and other common reproductive health services from a private doctor or family planning clinic.[g]

As noted above, most opportunity youth have access to insurance and a regular health care provider, indicating that many can be (and are being) served through the health care system. However, compared to female opportunity youth with consistent health insurance, those who lacked insurance at some point during the past year had a lower likelihood of accessing SRH services (65% versus 70%) and using a hormonal or long-acting method at last sex (35% versus 48%).

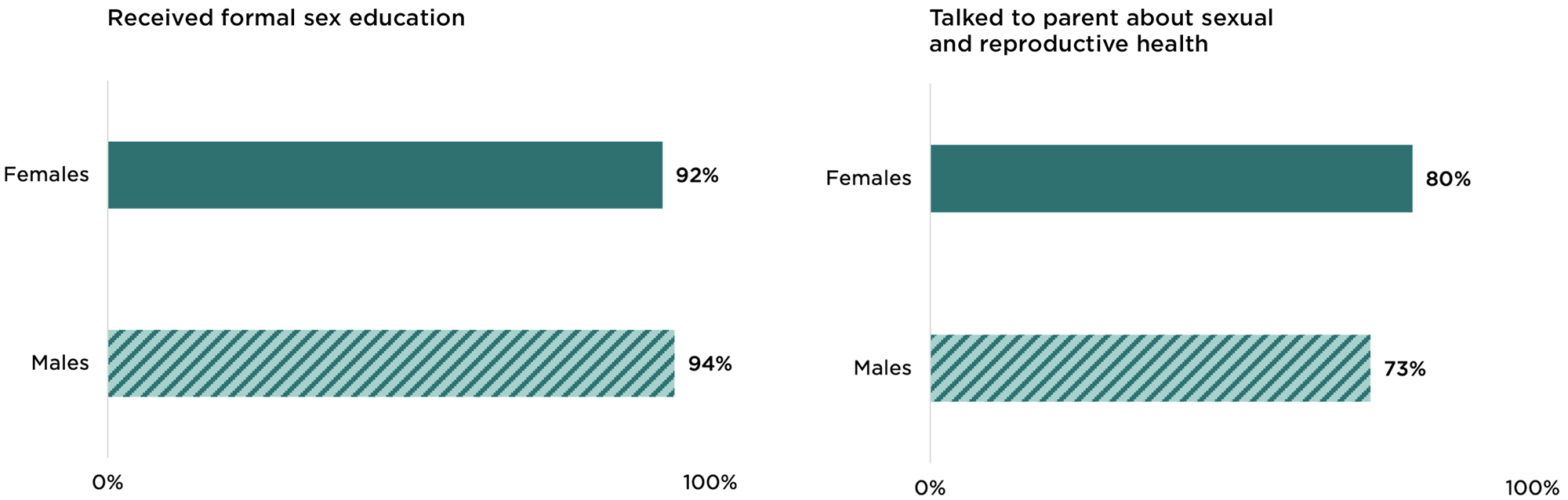

Most opportunity youth have received formal and informal sex education. Despite their current disconnection from school and work, the vast majority of opportunity youth reported (over 90%) receiving comprehensive sex education in school or a community setting before age 18. Additionally, 80 percent of female opportunity youth and 73 percent of their male counterparts have talked to their parents about SRH topics such as STIs/HIV, how to use a condom, and where to get birth control. As we described previously, many opportunity youth (particularly those ages 18 and younger) live with a parent, suggesting that one key way for youth-serving professionals to reach these youth may be through their families.

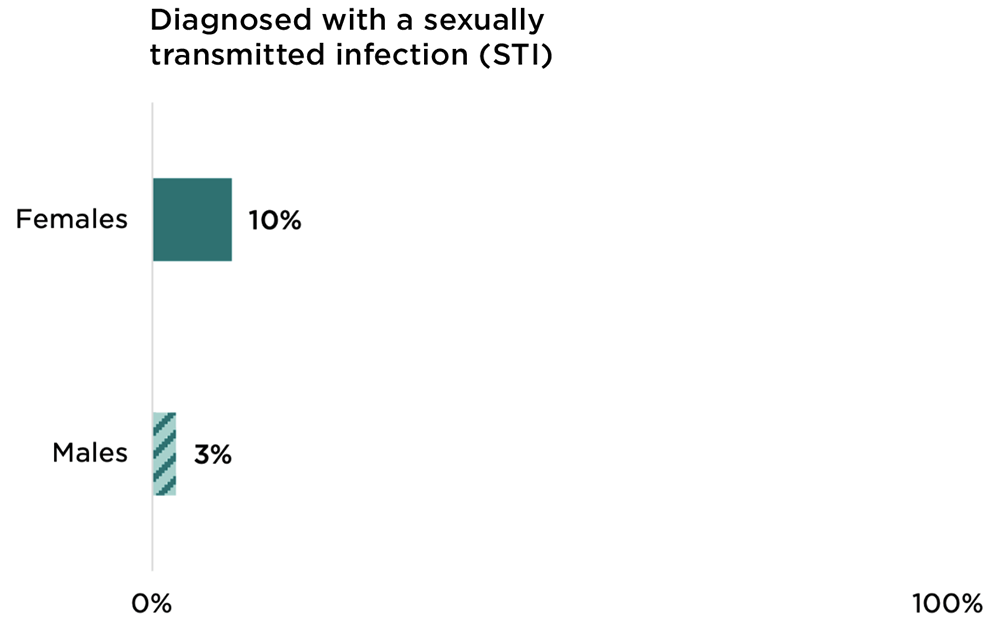

STI diagnosis is not common among opportunity youth. Ten percent of female opportunity youth and 3 percent of their male counterparts reported ever being diagnosed with herpes, syphilis, or genital warts, or having been diagnosed with gonorrhea or chlamydia in the past year. These rates are comparable to those seen among youth who are enrolled in school or working. (However, we note that measures of STI diagnosis can be incomplete since youth who are not tested cannot be diagnosed.)

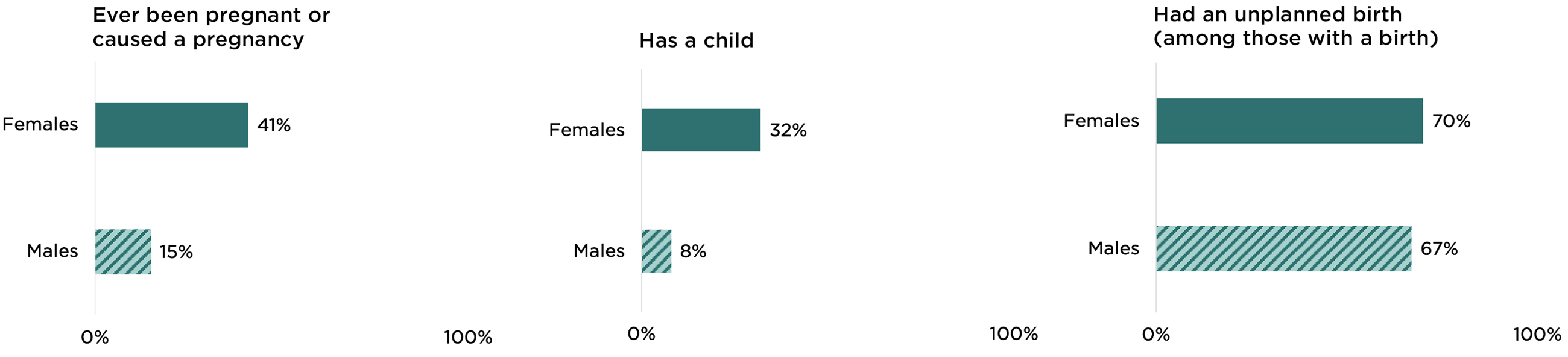

Pregnancy and parenthood are common among female opportunity youth. Forty-one percent of female opportunity youth reported ever being pregnant and nearly one third (32%) reported having given birth.[h],[i] By contrast, their more connected peers reported rates of 20 percent and 14 percent, respectively. Fifteen percent of male opportunity youth reported ever causing a pregnancy and 8 percent reported having fathered a child. The majority of both female and male opportunity youth who had given birth or fathered a child reported that at least one birth had been unplanned (70% of females and 67% of males).[j]

Although we do not know whether the opportunity youth in our analysis were disconnected from school and work prior to giving birth, three quarters (74%) of female opportunity youth with a child first gave birth two or more years prior to the survey. This indicates that having a child may have led to their leaving school or work (rather than the other way around). Other research has highlighted the challenges that young parents—especially mothers—face in trying to remain connected to school and work, including a lack of reliable and affordable child care.[5]

Summary and Implications

Findings from our analysis highlight several important things to know about the SRH of opportunity youth:

- Much like their more connected peers, most opportunity youth are sexually active, use effective contraception, and have received formal or informal sex education. Additionally, the majority of female opportunity youth access SRH care services.

- Female opportunity youth are more than twice as likely as their more connected peers to have experienced a pregnancy and to have a child. This points to the need for policies and programs to help young parents complete their education or obtain and maintain employment.

- Opportunity youth are a diverse group of young people who may need different types of support.

- Youth who live in households with lower incomes and/or those who lack health insurance may experience more financial barriers to accessing SRH care.

- Opportunity youth who are parenting have unique barriers to accessing health care (such as lack of child care or stigma from providers) but may have access to other support services.

- Because a disproportionate share of opportunity youth do not identify as straight, a heteronormative approach to SRH education and service provision may be particularly ineffective, or even damaging, for many young people in this population.

- Future research should explore how SRH outcomes may be different for subgroups (e.g., youth living in poverty, young parents, LGBTQ+ youth) within the diverse population of opportunity youth.

Suggested citation: Welti, K., Beckwith, S. & Murphy, K. (2022). Understanding the Sexual and Reproductive Health of Opportunity Youth. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. https://activatecenter.org/resource/understanding-sexual-reproductive-health-opportunity-youth

Footnotes

[a] When weighted, population estimates from the NSFG 2011-2019 are representative of 2015.

[b] For this analysis, we defined opportunity youth as young people, ages 16 to 24, who were not in enrolled in school and not working in the past week. Youth who were not enrolled in school and indicated they were “not working but looking for work,” “keeping house,” “caring for family” and “other” were considered opportunity youth. Those who were on vacation from school or on temporary leave from work due to family leave, vacation, strike, or illness were not considered opportunity youth. Additionally, those who were married with one or more children in the household were not considered opportunity youth.

[c] The NSFG only captures whether respondents’ reported gender is male or female. We therefore report on the respondents’ gender as documented in the data and acknowledge that these data and the analysis we present likely miss individuals who identify as neither male nor female.

[d] The NSFG does not measure whether respondents are transgender. Therefore, we use the acronym LGBQ instead of LGBTQ to accurately reflect what is reported in the data.

[e] This measure is limited to respondents ages 18 and older. For female respondents, forced sex refers to forced vaginal intercourse with a male partner. For male respondents, forced sex could include being forced to have vaginal sex with a female or anal or oral sex with a male.

[f] Youth who had sex with an opposite-sex partner in the last year were included in this analysis.

[g] We do not have a comparable measure of SRH care for males.

[h] Research has found that pregnancies that do not end in birth are underreported in the NSFG, so the incidence of pregnancy could be higher than estimated.

[i] As noted in the Methods box below, respondents who were not enrolled or working but were married with a young child were excluded from the sample of opportunity youth. This approach follows as closely as possible other U.S. research on opportunity youth.

[j] A birth is considered unplanned if the respondent reported that the pregnancy was unwanted, occurred too soon, or was mistimed.

-

Methods

-

References

-

Acknowledgements